NY 421 Tax Benefit

Introduction

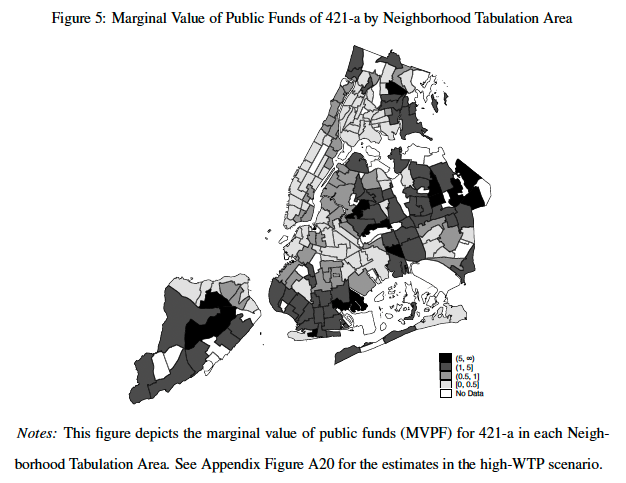

Soltas (2022) calculates the MVPF of Section 421-a of the New York State Real Property Tax Law. 421-a is partial exemption from property taxation primarily intended to encourage the provision of units for low-income individuals. The exemption is given to multifamily residential buildings where at least one in five units are designated for low-income tenants who pay below-market rents (‘inclusionary’ units). The exemption can last between 10 and 25 years after construction. In 2019, the accounting cost of 421-a was $1.6 billion. The paper estimates the MVPF of the 421-a exemption separately for each of 179 neighborhoods in New York City. The paper finds that some neighborhoods are ‘opportunity bargains’ with low fiscal costs and high benefits, while other neighborhoods have very low (or zero) benefits per dollar of fiscal cost.

MVPF = 0.5

Net Cost

There are two components to the cost estimates: the direct cost and the fiscal externality. Soltas calculates the direct cost by assuming a small change in the 421-a incentive and estimating, for a given neighborhood, the ratio of the resulting change in 421-a tax expenditure to the change in the number of inclusionary units. To calculate the fiscal externality, the paper calculates how the increase in earnings due to neighborhood residence impacts the government’s budget. He adapts the approach of Hendren and Sprung-Keyser (2020) to the context of New York City, incorporating data on New York City’s labor income tax schedule, age-specific earnings profiles, estimates of income mobility, and specific characteristics of 421-a.

The mean net cost based on quartile of neighborhood MVPF distribution is (with standard errors in parentheses):

- $217,088 ($4,842)

- $204,675 ($2,248)

- $79,641 ($861)

- $19,139 ($466)

Willingness to Pay

There are two components of willingness to pay for 421-a in a given neighborhood: (1) the direct willingness to pay for housing in that neighborhood, and (2) any increase in future after-tax income for children who grow up in that neighborhood. For (1), households value the inclusionary unit at the minimum of how much they would have spent on their counterfactual housing and the amount of tax savings that would make the developer indifferent between including the unit or not (i.e., the developer+AC100s ‘breakeven’). The estimated increases in future after-tax income are calculated based on the benefits to individuals of relocating to specific neighborhoods using the procedure from Bergman, Chetty, deLuca, Hendren, Katz, and Palmer (2020).

The mean willingness to pay based on quartile of neighborhood MVPF distribution is (with standard errors in parentheses):

- $45,269 ($1,222)

- $96,934 ($956)

- $72,655 ($660)

- $58,288 ($487)

MVPF Summary

The paper calculates the MVPF on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis. The by-neighborhood MVPF of using 421-a to add inclusionary housing ranges from approximately 0 to above 5. This variation is driven both by differences in housing costs across neighborhoods and by differences across neighborhoods in their causal impact on upward mobility.

Dividing the mean willingness to pay by the mean net cost based on quartile of neighborhood MVPF distribution yields:

- 0.209

- 0.473

- 0.9124

- 3.046

Figure 5 from the paper (below) shows the full distribution of neighborhood-specific MVPFs.

References

Bergman, Peter, Raj Chetty, Stefanie deLuca, Nathaniel Hendren, Lawrence F. Katz, and Christopher Palmer (2020). “Creating Moves to Opportunity: Experimental Evidence on Barriers to Neighborhood Choice.” NBER Working Paper 26164. https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/cmto_paper.pdf

Hendren, Nathaniel and Ben Sprung-Keyser (2020). “A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(3): 1209–1318. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa006

Soltas, Evan (2022). “The Price of Inclusion: Evidence from Housing Developer Behavior.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 1-46: https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01231

Policy Features

- Category

- In Kind Transfers

- Sub-Category

- Housing

- Beneficiary Type(s)

- Adults, Firms, People receiving housing assistance

- Country of Implementation

- United States

- Year of Implementation

- 2009

- Empirical Method

- Difference in Differences

- Research Type

- Primary

- Peer Reviewed

- No

- MVPF Publication Link

- doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01231